A film about a machine and the people who use, love and repair it.

30+ interviews in 10 U.S. states with authors, collectors, journalists, professors, bloggers, students, artists, inventors and repairmen (and women) who meet up for ‘Type-In’ gatherings to both celebrate and use their decidedly lo-tech typewriters in a plugged-in world.

The film features authors Robert Caro and David McCullough – 4 Pulitzer Prizes, 3 National Book Awards and a Presidential Medal of Freedom between them – both typewriter users. They have a lot to say about process and the value of slowing down, writing actual drafts and revising in a world of instant, draft-less editing.

The film was inspired by a May, 2010 article in Wired magazine called “Meet The Last Generation of Typewriter Repairman.” Director Christopher Lockett and Producer Gary Nicholson discussed the importance of the typewriter in 20th Century literature. The conclusion being that every great novel of the 20th Century was written on one, and if typewriters are in their final days, they deserved to be celebrated one last time.

It only took a few interviews to determine that the typewriter and its legion of fans is far from dead. By the time the “Last Typewriter Factory Closes Its Doors” article went viral in April of 2011, Lockett and Nicholson were not only already making the film, they were convinced they had a much bigger story on their hands. They did.

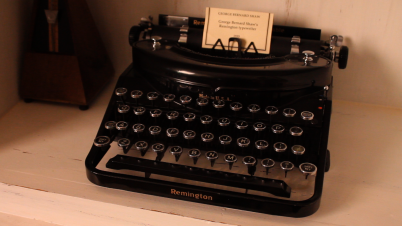

Funded largely through Kickstarter, the film eventually featured not only typewriter people – the aforementioned technicians, collectors, bloggers, users and fans – but famous typewriters as well. The film features machines once owned by Ernest Hemingway, Jack Kerouac, Tennessee Williams, John Steinbeck, Jack London, Sylvia Plath, George Bernard Shaw, John Lennon, Joe DiMaggio, Helen Keller, The Unabomber, John Updike, Ray Bradbury and Ernie Pyle.

While the film’s budget was meager and about as independent as filmmaking gets, its scope is broad and deep. To borrow a phrase from boxing, it punches above its weight. Discussions range from American manufacturing – David McCullough has typed everything he has ever written on the same machine, one he has owned since 1965 – to the philosophy of the creative mind.

Richard Polt, Chair of the Philosophy Department at Xavier University and chief figure in the Typosphere, an online community of bloggers, collectors and enthusiasts, likens using a typewriter to riding a bicycle. “It’s about enjoying the ride. I think typewriters will persist… as a healthy, meaningful alternative to the most efficient way of doing things.”

Author Lynn Peril talks about the early history the machine and how the word “typewriter” described both the machine and the person using it: “The typewriter is the one piece of office technology that allowed women to move from the home to the professional work force.”

Manson Whitlock, at age 95 the oldest person in the film and likely the oldest working typewriter repairman in America, is blunt about it: “I think that something that was made to be thrown away ought never to have been made at all.”

For Arizona high school English teacher Ryan Adney, who uses typewriters in his classroom, an essential part of a writer’s process is revision. “That process is lost when you’re editing on the fly,” he says. “And you’re working without a net,” he says, “no spell check. I’ve measured a 68-72 percent improvement in my students spelling abilities once they started using typewriters.”

For soldiers Peter Meijer and Alan Beck, sending typewritten letters from the front lines in Afghanistan and Iraq was a very different way of communicating than email. Meijer said: “One woman I sent letters to, when I visited her on leave, carried those letters around with her in her purse. You don’t get that with email.”

Lockett was surprised that Jack Zylkin, inventor of the USB Typewriter – a modification that allows a manual typewriter to be used with an iPad or any computer monitor with a USB input – is something of a technophobe. An electrical engineer by training, Zylkin “couldn’t stand interfacing with a screen all day and then doing it again when I came home.” A typewriter lover, he said his invention “is less about updating the typewriter and more about re-introducing a wonderful machine that still works, to this generation.”

The repairmen who keep these venerable old machines oiled, inked and click-clacking along are of course happy to see a renewed interest in the typewriter. But they know more than most, as repairman Ermanno Marzorati says, “the enemy is time.” New typewriter parts are just hard to come by.

Repairmen Ruben Flores and Bill Wahl talk about the inventory of older machines they have to cannibalize to keep customers’ machines working. Even award-winning writer Robert Caro isn’t immune to the ravages of time: “When I started the last book, I had 17. I’m down to 11 now,” Caro says.

But, as blogger Michael Clemens points out, “Typewriters were designed to be your lifetime machine. The longest I’ve had a laptop work was for nine years. Yet I have typewriters that are more than 50 years old and I write with them every day.”

Alaska-based singer-songwriter Marian Call uses a typewriter as a percussion instrument. “Nothing else makes that sound. And it brings with it a flood of memories,” she says. “When I first took the typewriter out on tour, only a few people had them. But this last tour, a lot of people had them. When I asked them ‘Why?’ they all said ‘Because typewriters don’t have Facebook.’ “

That is a recurring theme of the film – people need a place to unplug and be alone with their thoughts. A typewriter offers that – and the same QWERTY keyboard that’s on our laptops and smart phones. As author Darryl Rehr points out, “That QWERTY keyboard came out of the Remington plant in 1874.”

For a 19th Century invention, the typewriter and the typewriter scene the film documents is surprisingly vital

[…] as I was promoting this post on Twitter, I stumbled on a new film coming out featuring typewriters: The Typewriter in the 21st Century. I want to work on getting a screening in Irvine; it looks so interesting! I love the quote […]

LikeLike